Miami vibrates with color and bright nightlife. And below the surrounding coastal waterline, coral reefs play out their own neon dramas that rival those of the city. Making these similarities obvious to the public is the aim of the art duo called Coral Morphologic. Musician J. D. McKay and marine biologist Colin Foord collaborate and use footage of coral from Florida and around the world in video, multimedia and art installations. Their goal is to help viewers appreciate and want to protect this vital underwater ecosystem. The duo’s brilliantly hued work has appeared inside and on exhibit halls. No, really: Coral Morphologic has projected images of fluorescent red and green polyps over entire buildings in Miami.

In recent years, coral surrounding Miami has begun growing on local seawalls, and Coral Morphologic hopes this is a sign of the creatures’ resilience in the face of changing ocean conditions. These pioneering corals “may hold the keys to understanding how reef organisms worldwide may adapt to human influence in the 21st century,” the collaborators share in a statement. If corals can find a way to thrive on the rapidly changing Miami coastline, then where else might they manage to persist?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

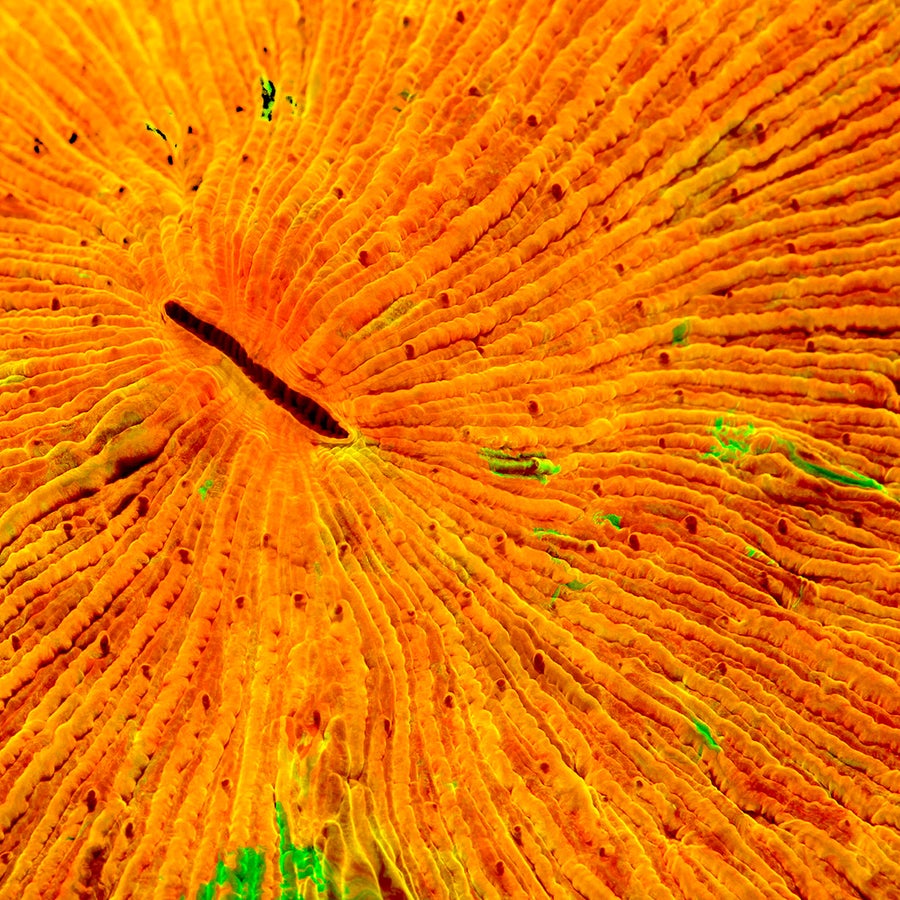

Corals eat more than just microscopic creatures called zooplankton. Here, a Fungia coral in the Indo-Pacific sneaks its mouth around a fish head. Other members of the genus in the Red Sea have been spotted dining on jellyfish half their size.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

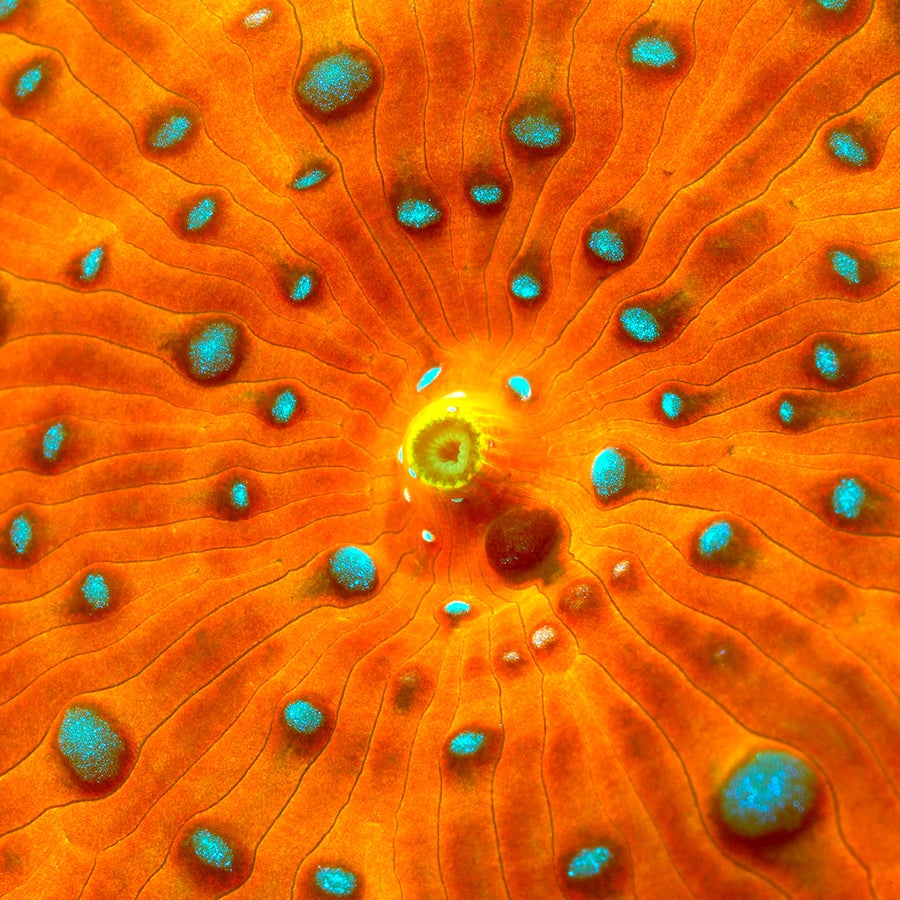

The mouth of a Cycloseris coral found in an Indo-Pacific reef. Meals disappear into the gastrovascular cavity, which is also where the equivalent of digestive cells empty their waste.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

A close-up of coral belonging to the Echinophyllia genus found in the Indo-Pacific.. Many of these coral varieties grow like a carpet coating rocky surfaces on a reef. The tactic makes the Echinophyllialess susceptible to storm damage compared to their vertical, branching relatives.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

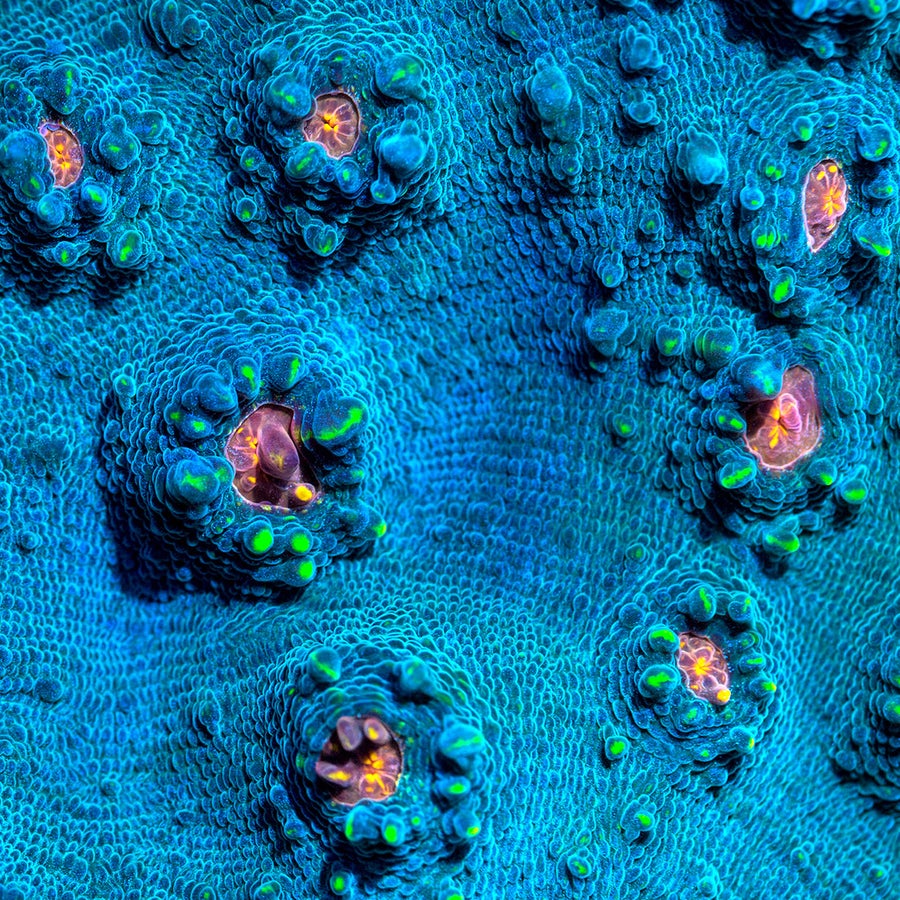

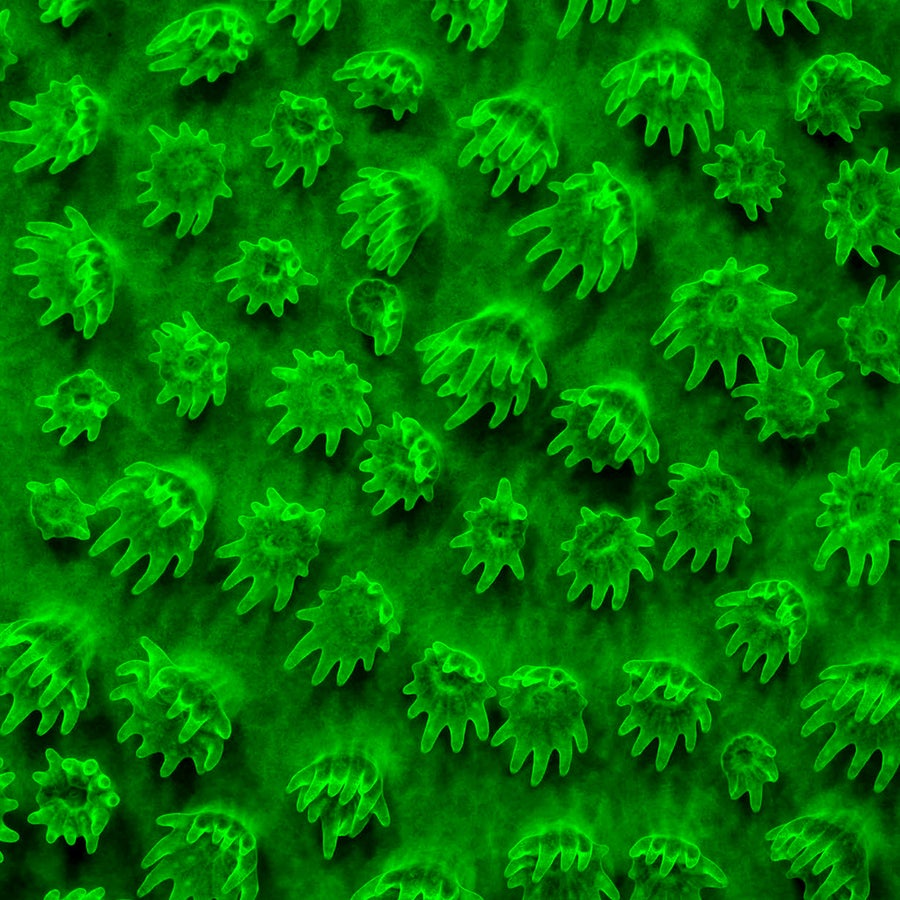

Neither jellyfish, coral or anemone, this organism, known as a corallimorph, is one of the lesser-known members of the Cnidaria phylum and shown here in a fluorescence photo. In 2007, researchers found a particular corallimorph smothering reefs at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, possibly attracted by the degrading iron from buoys and a nearby shipwreck.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

Ricordea florida, the species shown here, has been the victim of illegal wildlife harvesting in both Florida and Puerto Rico.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

A Phymanthus crucifer anemone, which could be found attached to a reef around Florida, unfurls its tentacles. Each tendril is lined with special cells that launch piercing or adhesive bits into passing prey.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

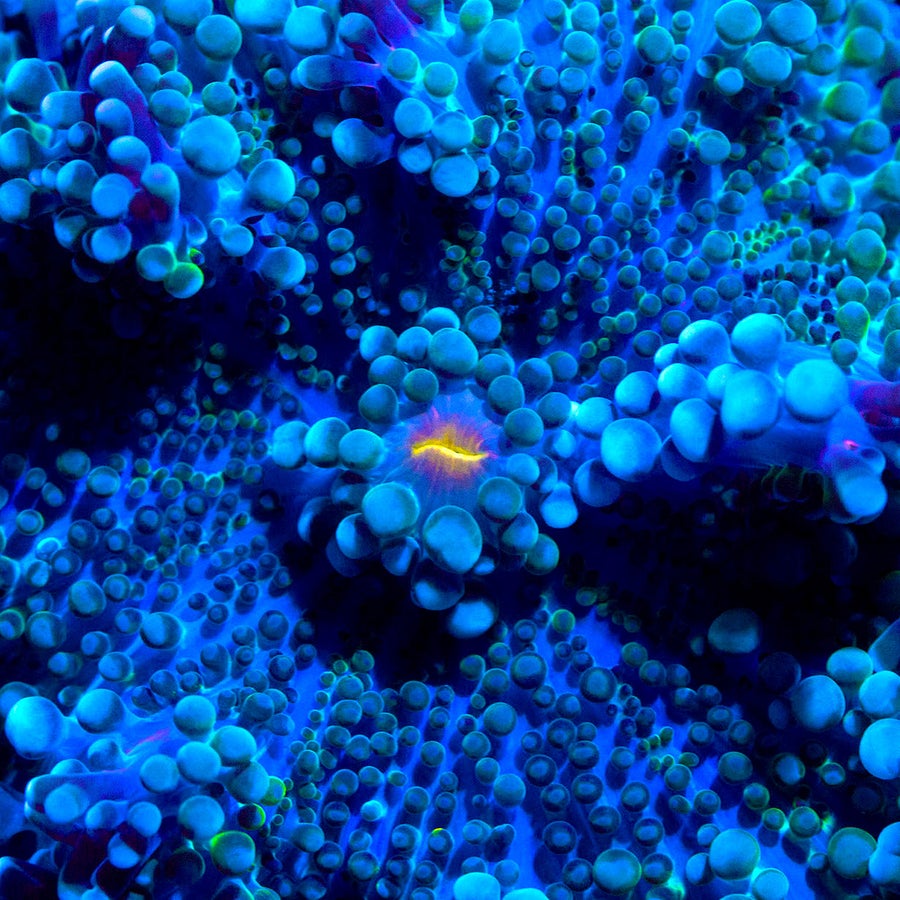

The mouth of a corallimorph known as Ricordea yuma, found in the Indo-Pacific. Corallimorphs can’t build their own exoskeletons, but are closely related to corals that can. Scientists are struggling to figure out why the two cnidarian varieties evolved differently on this crucial trait.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

An astreoides coral. This variety belongs to a larger group of “stony” corals, meaning each polyp pushes out calcium carbonate to create a durable underlying structure. The compound is otherwise known as limestone, and constitutes each Florida Keys island—meaning human residents live atop long-dead coral reefs.

Credit: Coral Morphologic

If it took you a minute to distinguish the seahorse from the coral, that’s exactly the effect the pregnant male was going for. These centimeter-long Pygmy seahorses live exclusively amongst gorgoniansea fan corals.