October 1967

Shantytowns: Unseen Structure and Evolution

“The common view is that the squatters populating the Peruvian shantytowns are Indians from the rural mountains who still speak only the Quechuan language, that they are uneducated, unambitious, disorganized, an economic drag on the nation—and also that they are a highly organized group of radicals who mean to take over and communize Peru's cities. I found that in reality the people of the barriadas around Lima do not fit this description at all. Most of them had been city dwellers for some time (on the average for nine years) before they moved out and organized the barriadas. They speak Spanish (although many are bilingual); indeed, their educational level is higher than that of the general population in Peru. At first glance the barriadas appear to be formless collections of primitive straw shacks. Actually the settlements are laid out according to plans, often in consultation with architectural or engineering students. As time goes on most of the shanties are replaced by more permanent structures.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

October 1917

Volcano Power

“In central Tuscany in 1906, volcanic steam was first used in an ordinary steam engine of about forty horse-power, but the borax salts and other accompanying chemicals seriously corroded the machinery. Then the superheated steam was applied to an ordinary multitubular boiler in which it was used in place of fuel. An experimental plant worked successfully, supplying power to the works and the villages around Lardarello. Its success led Prince Ginori-Conti to develop a power plant on a large scale, and three 3,000-kilowatt turbogenerators were installed in 1916. The new undertaking has proved a great boon in industrial Tuscany, where the present war-price of coal ranges from $40 to $50 per ton.”

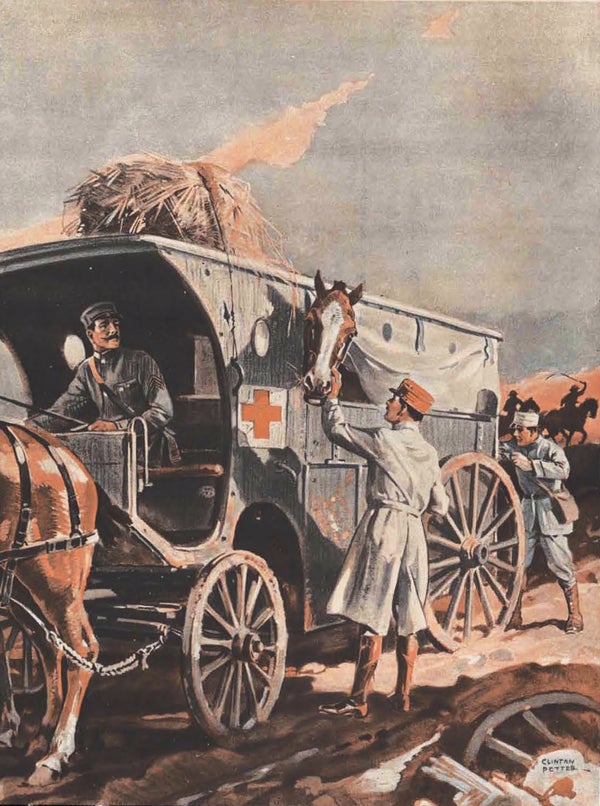

Warhorses

“Like everything else, horses and mules are found in this war in numbers never before approached. As it has been necessary to exercise greater scrutiny of resources in every direction, it has been essential that the ultimate pound of energy be obtained from every animal, that no mount or beast of burden be permitted to go into the last discard until every expedient to save him has been exhausted. For horses are scarce; no longer can the army chief shoot them or work them to death or turn them off with calm confidence that plenty more are to be had. Rather he must conserve them in every possible way; and so we have the field hospital for horses, illustrated here.”

More archive images on the horse in the First World War can be found at www.ScientificAmerican.com/oct2017/warhorse

October 1867

Quinine for Malaria

“Among the many remedial agents which organic chemistry has afforded us, quinine occupies the first place, chloroform the second. Without quinine, large tracts, indeed whole countries, would be simply uninhabitable for Europeans. The ‘quinine famine’ in the Mauritius demonstrated to thousands how small a thing even gold itself might become in comparison with this lifesaving salt. The search for artificial quinine, though, has been as unsuccessful as that for the Philosopher's Stone. This circumstance has induced certain enterprising men to cause the cinchonas to be introduced into India, and the cinchona plantations in India are now so flourishing that there need be no apprehension of the supply of quinine ever failing.”

Be Careful What You Wish For

“Why should not every house have its telegraphic wire? When gas was first applied to purposes of illumination it was used only in the public buildings and streets, and even now on the continent of Europe it has been introduced but sparingly into private dwellings. Why may not the telegraph wire be extended and diffused as the gas pipe has been? Suppose a network of such wires laid from a central point in the city to the library or sitting room of every dwelling, and an arrangement made for collecting news similar to that controlled by the associated press. Through the wires, then, this news might be instantly communicated to each family. A fire, a murder, a riot, the result of an election, would be simultaneously known in every part of the city. Of course, this would do away with newspapers, but what of that? All things have their day, and why should such ephemeral things as newspapers be an exception to the rule?”