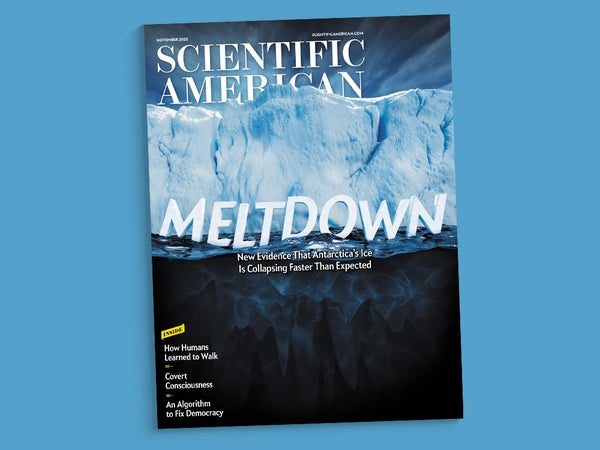

The Thwaites Ice Shelf is one of the most important geological features on the planet, and it’s in trouble. The 800-square-kilometer slab of ice floats in front of Antarctica’s enormous Thwaites Glacier and braces it in place. In the past few years scientists have found new ways the ice shelf is melting, cracking and wobbling. Science journalist Douglas Fox accompanied researchers as they pulled sleds full of radar equipment across the ice to study its interior, finding surprises with every new observation. The consequences of a Thwaites Ice Shelf collapse would be catastrophic, flooding coastal towns around the world, and it could start to crumble in a decade.

The implications of Thwaites research are grim, but the article about it is actually a lot of fun. The details make the story: Antarctic ice that crunches like cornflakes, the snowy fuff when scientists detonated explosives, and the possibility that on a future mission, scientists will wake up to find themselves unexpectedly floating on an iceberg.

The editors at Scientific American encourage our authors to share the amusing, weird, awe-inspiring, scary, human side of science in their stories. Paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva really came through for us, with a memorable anecdote about researchers playing dodgeball with elephant dung before they discovered an important bed of fossilized footprints. I laughed out loud when I read his methodology for a research project that involved applesauce (I won’t spoil it). The fascinating conclusion to all this Very Serious Research is that humans learned to walk many times in our evolutionary history, with very different gaits and postures. When multiple hominin species lived in the same place, they might have been able to tell one another apart from a distance based on how they walked.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

New techniques for assessing brain activity are revealing that some patients who appear to be in a coma or unresponsive can understand some of what’s happening around them. Detecting “covert consciousness” can help guide treatments and predict clinical outcomes. Neurologists Jan Claassen and Brian L. Edlow are working to improve methods of testing for covert consciousness, and they explore what it means for our understanding of consciousness itself.

Subatomic particles appear to be breaking a rule called “lepton flavor universality.” Physicists are getting really excited about their strange behavior, and I hope you will, too, after you read theoretical physicist Andreas Crivellin’s story. The Standard Model has been extremely successful at helping us understand the subatomic world, but it doesn’t explain everything. Strangely behaving particles have the potential to reveal what’s wrong or what’s missing from our understanding of everything from neutrinos to dark matter.

Certain newly invented materials behave strangely as well. Some of these “metamaterials” bend light in unusual ways, cloaking an object to make it invisible. They’re engineered at the nanoscale, with a range of features that bend light and sound to their whim. Physicist and engineer Andrea Alù describes how metamaterials can support superconductivity and break symmetries.

Citizens’ assemblies are groups of people who work together to understand a problem, find solutions and build consensus, especially for divisive issues. They’ve been around since ancient Greece, but they’re becoming more popular lately. These assemblies are much more inclusive and representative than representative democracy, but the process of choosing participants can still be tricky. Computer scientist Ariel Procaccia shares his work on creating and refining an algorithm for democracy.